Paper: Testing General Relativity Using Golden Black-Hole Binaries

This post describes a paper outlining the methodology for testing general relativity with binary black holes, which was later applied to the LIGO and Virgo detections of these systems.

Paper Highlighted

- Ab. Ghosh, Ar. Ghosh, N. K. Johnson-McDaniel, C. K. Mitra, P. Ajith, W. Del Pozzo, D. A. Nichols, Y. Chen, A. B. Nielsen, C. P. L. Berry, and L. London. “Testing general relativity using golden black-hole binaries.” Phys. Rev. D 94, 201101 (2016), arXiv:1602.02453.

Summary of the Paper

The merger of a black-hole binary releases an enormous amount of energy that is carried off by gravitaitonal waves.

Before the detections of binary black holes and neutron stars by the LIGO and Virgo Collaborations, general relativity had not been well tested for this aspect of the theory.

Einstein’s theory turns out to describe the merger of these black holes well, but it is important to be able to quantitatively test whether any deviations might occur.

The merger of a black-hole binary releases an enormous amount of energy that is carried off by gravitaitonal waves.

Before the detections of binary black holes and neutron stars by the LIGO and Virgo Collaborations, general relativity had not been well tested for this aspect of the theory.

Einstein’s theory turns out to describe the merger of these black holes well, but it is important to be able to quantitatively test whether any deviations might occur.

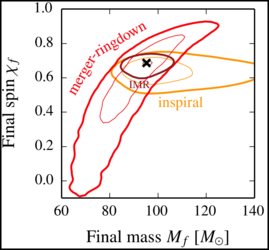

We propsed a test of general relativity that was similar to one proposed by Hughes and Menou for so-called golden binaries: supermassive black-hole binaries that could be observed with very high signal-to-noise ratio by the proposed space-based detector, LISA. Here, we plan to determine the masses and spins of the stellar-mass black holes seen by LIGO and Virgo during their inspiral (prior to merger) and independently determine the final mass and spin of the black hole using only the merger and ringdown part of the waveform after the inspiral. Numerical relativity simulations predict a relationship between the initial and final masses and spins. Thus, we can use these relationships to determine if our predictions of the final masses and spins from the inspiral and the merger and ringdown, respectively, give rise to estimates that are consistent the the results of general relativity.

The figure shows the results from a simulation of a binary black hole with equal masses and total mass equal to one-hundred solar masses. The predictions from the inspiral, the merger and ringdown, and the complete gravitational waveform are all consistent within their errors. Because the posterior distributions of the parameters are spread over a large range of the parameter space, a single measurement will not give very strong constraints on general relativity. However, if we chose parameters that are the fractional deviations from the results of general relativity, we can combine the posteriors from multiple different events to get a much stronger constraint, once many black-hole binary mergers are discovered. This test has been applied to several of the LIGO and Virgo detections to show that the observed waveforms agree with the predictions of general relativity to within around ten percent.