Research Theme: Visualizing Spacetime Curvature with Vortex and Tendex Lines

This post is a summary of six papers I wrote with collaborators during my Ph.D. about visualizing spacetime curvature around binary-black-hole mergers.

Papers Highlighted

-

R. H. Price, J. W. Belcher, and D. A. Nichols. “Comparison of electromagnetic and gravitational radiation; what we can learn about each from the other.” Am. J. Phys. 81, 575 (2013), arXiv:1212:4730,

-

D. A. Nichols, A. Zimmerman, Y. Chen, G. Lovelace, K. D. Matthews, R. Owen, F. Zhang, and K. S. Thorne. “Visualizing spacetime curvature via frame-drag vortexes and tidal tendexes: III. Quasinormal pulsations of Schwarzschild and Kerr black holes.” Phys. Rev. D 86, 104028 (2012), arXiv:1208.3038.

-

F. Zhang, A. Zimmerman, D. A. Nichols, Y. Chen, G. Lovelace, K. D. Matthews, R. Owen, and K. S. Thorne. “Visualizing spacetime curvature via frame-drag vortexes and tidal tendexes: II. Stationary black holes.” Phys. Rev. D 86, 084049 (2012), arXiv:1208.3034.

-

D. A. Nichols, R. Owen, F. Zhang, A. Zimmerman, J. Brink, Y. Chen, J. D. Kaplan, G. Lovelace, K. D. Matthews, M. A. Scheel, and K. S. Thorne. “Visualizing spacetime curvature via frame-drag vortexes and tidal tendexes: I. General theory and weak-gravity applications.” Phys. Rev. D 84, 124014 (2011), arXiv:1108.5486.

-

A. Zimmerman, D. A. Nichols, and F. Zhang. “Classifying the isolated zeros of asymptotic gravitational radiation by tendex and vortex lines.” Phys. Rev. D 84, 044037 (2011), arXiv:1107.2959.

-

R. Owen, J. Brink, Y. Chen, J. D. Kaplan, G. Lovelace, K. D. Matthews, D. A. Nichols, M. A. Scheel, F. Zhang, A. Zimmerman, and K. S. Thorne. “Frame-dragging vortexes and tidal tendexes attached to colliding black holes: Visualizing the curvature of spacetime.” Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 151101 (2011), arXiv:1012.4869.

Summary of the Papers

In empty space, the ten independent components of the Weyl tensor encode all the information about the spacetime curvature, but the Weyl tensor itself is difficult to visualize and to grasp its physical meaning.

The Weyl tensor in a surface of constant time splits into two symmetric and trace-free tensors called its electric and magnetic parts (in analogy to the E and B fields of electromagnetism).

The interpretation of the electric and magnetic Weyl tensors has been known for quite some time: the electric part describes the tidal acceleration of two spatially separated observers, and the magnetic part relates to the differential precession of two adjacent inertial gyroscopes.

In empty space, the ten independent components of the Weyl tensor encode all the information about the spacetime curvature, but the Weyl tensor itself is difficult to visualize and to grasp its physical meaning.

The Weyl tensor in a surface of constant time splits into two symmetric and trace-free tensors called its electric and magnetic parts (in analogy to the E and B fields of electromagnetism).

The interpretation of the electric and magnetic Weyl tensors has been known for quite some time: the electric part describes the tidal acceleration of two spatially separated observers, and the magnetic part relates to the differential precession of two adjacent inertial gyroscopes.

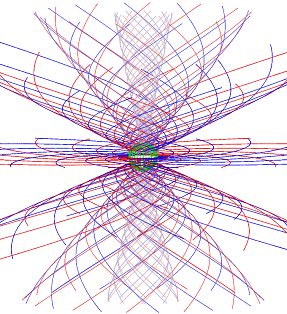

To visualize the Weyl tensor’s electric and magnetic parts, we used the facts that these tensors are always diagonalizable, the sum of their eigenvalues will be zero, and the corresponding eigenvectors are orthogonal. We formed streamlines from the eigenvectors, which we call tendex lines for the electric part and vortex lines for the magnetic part, and we plotted these lines and their corresponding eigenvalues, which we call tendicities and vorticities, respectively. Extended observers are stretched along a tendex line with negative tendicity and squeezed along a tendex line of positive tendicity; similarly, observers with gyroscopes tied to their heads and feet are twisted clockwise along a positive-vorticity vortex line and counterclockwise along a negative-vorticity line.

We applied these vortex and tendex concepts in several directions. To build up intuition about these new visualizations, we looked at well-known examples of stationary and radiating spacetimes. In particular, we investigated the vortexes and tendexes of weakly-gravitating stationary spinning and non-spinning point particles, multipolar gravitational waves, and binaries made of spinning and non-spinning point particles. We were able to understand the generation of gravitational waves in terms of vortexes and tendexes in the near zone that induce accompanying tendexes and vortexes to form those of gravitational waves. When we studied stationary and perturbed black holes, we found similar insights about the structure of the vortexes and tendexes and their roles in generating gravitational radiation. In addition, we found that tendex and vortex lines provide a framework to prove that gravitational radiation must vanish at isolated points far from their source. We also studied the similarities and differences between electromagnetic field lines and vortex and tendex lines.