Research Theme: Forecasts for detecting the gravitational-wave memory effect with current and future detectors

This post summarizes work on when the gravitational-wave memory effect and spin memory effect will be able to be detected by the Advanced LIGO and Virgo detectors, as well as planned gravitational-wave detectors, such as Cosmic Explorer.

Papers Highlighted

-

A. M. Grant and D. A. Nichols. “Outlook for detecting the gravitational wave displacement and spin memory effects with current and future gravitational wave detectors.” Phys. Rev. D 107, 064056 (2023), arXiv:2210.16266. Erratum: Phys. Rev. D 108, 029901 (2023).

-

O. M. Boersma, D. A. Nichols, and P. Schmidt. “Forecasts for detecting the gravitational-wave memory effect with Advanced LIGO and Virgo.” Phys. Rev. D 101, 083026 (2020), arXiv:2002.01821.

Summary of the Papers

The gravitational-wave luminosity of a black-hole binary at its peak can be as high as a few thousandths of the fundamental unit of luminosity—the speed of light to the fifth power divided by Newton’s constant (c5/G)—the so-called Planck luminosity. One consequence of this high luminosity is that asymmetries in the distribution of energy radiated in gravitational waves produces secondary gravitational waves. Aspects of the gravitational waves produced through this mechanism are called the gravitational-wave memory effect, because they lead to a lasting change in the gravitational-wave strain that endures even after the gravitational-waves have passed. This lasting strain is typically a small fraction (around a twentieth) of the peak amplitude of the gravitation waves, and it is currently below the threshold of detection for individual binary-black-hole mergers. However, it had been shown previously that one could find statistical evidence for the gravitational-wave memory effect in a population of binary black holes like that of the first event detected, GW150914. For a population of these events, it was shown it would take fewer than one-hundred such events to find statistical evidence for the memory effect.

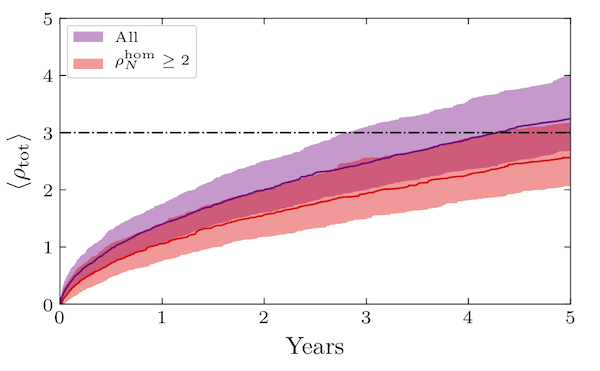

Subsequent gravitational-wave detections showed that the population of binary-black-hole mergers had a much wider range of distances and masses than the first event. Oliver Boersma in his MS thesis (supervised by Patricia Schmidt and me) then investigated how long it would take for advanced LIGO and Virgo to detect the memory effect from a population of binary black holes that was consistent with the population inferred from the first gravitational-wave catalog of events (GWTC-1). We found that the it would take closer to five years of observing runs (assuming the three detectors were operational in coincidence for half of the time) for LIGO and Virgo to detect the gravitational-wave memory effect. This is illustrated in the figure above, which shows how the signal to noise in the population (roughly the significance of the observation in units of standard deviations), accumulates as a function of time. Given the rate of events, it is then anticipated that it will take closer to one thousand detections to find evidence for the gravitational-wave memory effect. It is thus more likely to be discovered during the next upgrade of the LIGO and Virgo detectors after the detectors achieve their design sensitivity (when LIGO A+ and Advanced Virgo+ are operating).

In more recent work, Alex Grant and I revisited the forecasts for the detection of the gravitational-wave memory effect, because the rate of binary-black-hole mergers was determined more precisely after the many additional discoveries and improved modeling of the binary-black-hole population that occurred during LIGO’s third observing run. The LIGO A+ upgrade was also approved, which changed LIGO’s observing plans. We found that the memory effect would be likely to be detected for the population of black-hole mergers within a few years of LIGO A+ reaching its design sensitivity. For the next-generation gravitational-wave detector, Cosmic Explorer, this detector would likely detect the memory effect from a single, high signal-to-noise binary-black-hole observation. In addition, given the much larger number of detections of black-hole mergers, it could also detect the gravitational-wave spin memory effect from the large population of binary black holes measurable by Cosmic Explorer. These latter results for Cosmic Explorer highlighted the potential of the detector for making precision gravitational-wave measurements.