Research Theme: Dynamics of dark matter in intermediate mass-ratio inspirals

This post describes five papers on the dynamics of dark matter in intermediate mass-ratio inspirals (IMRIs), the gravitational waves emitted from these systems, and the prospects for detecting the dark matter using gravitational-wave observations with the planned detector LISA.

Papers Highlighted

-

B. A. Wade and D. A. Nichols. “Intermediate mass-ratio inspirals in a dense dark-matter environment: Effects of the initial dark-matter distribution,” (2025). arXiv:2508.21132.

-

E. Wilcox, D. A. Nichols, and K. Yagi. “Probing dark-matter effects with gravitational waves using the parametrized post-Einsteinian framework.” Phys. Rev. D 110, 124009 (2024), arXiv:2409.10846.

-

D. A. Nichols, B. A. Wade, and A. M. Grant. “Secondary accretion of dark matter in intermediate mass-ratio inspirals: Dark-matter dynamics and gravitational-wave phase.” Phys. Rev. D 108, 124062 (2023), arXiv:2309.06498.

-

A. Coogan, G. Bertone, D. Gaggero, B. J. Kavanagh, and D. A. Nichols. “Measuring the dark matter environments of black hole binaries with gravitational waves.” Phys. Rev. D 105, 043009 (2022), arXiv:2108.04154.

-

B. J. Kavanagh, D. A. Nichols, G. Bertone, and D. Gaggero. “Detecting dark matter around black holes with gravitational waves: Effects of dark-matter dynamics on the gravitational waveform.” Phys. Rev. D 102, 083006 (2020), arXiv:2002.12811.

Summary of the Papers

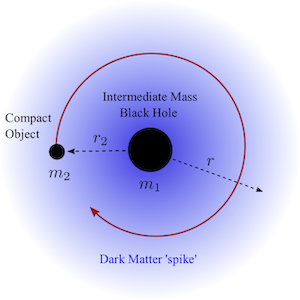

Black holes that form in dark-matter halos can slowly grow in mass over long timescales as they accrete and capture matter.

During this slow growth, the dark matter can redistribute around the black hole to produce a “spike” of high density close to the black hole that falls off rapidly with radius.

If an intermediate mass (thousands to hundreds of thousands of solar masses) black hole with such a “dress” of dark matter around it, then it could capture a stellar mass (tens of solar masses) black hole or a neutron star to form an intermediate mass-ratio inspiral (IMRI).

IMRIs with and without the surrounding dark-matter dress have quite different orbital dynamics.

In particular, the dark matter adds an additional drag force (dynamical friction) that causes the small black hole or neutron star to inspiral much more rapidly than it would if gravitational waves were the only source of energy loss from the system.

Previous work had shown that this allows the dark matter distribution to be mapped out precisely by the inspiralling neutron star or small black hole.

Black holes that form in dark-matter halos can slowly grow in mass over long timescales as they accrete and capture matter.

During this slow growth, the dark matter can redistribute around the black hole to produce a “spike” of high density close to the black hole that falls off rapidly with radius.

If an intermediate mass (thousands to hundreds of thousands of solar masses) black hole with such a “dress” of dark matter around it, then it could capture a stellar mass (tens of solar masses) black hole or a neutron star to form an intermediate mass-ratio inspiral (IMRI).

IMRIs with and without the surrounding dark-matter dress have quite different orbital dynamics.

In particular, the dark matter adds an additional drag force (dynamical friction) that causes the small black hole or neutron star to inspiral much more rapidly than it would if gravitational waves were the only source of energy loss from the system.

Previous work had shown that this allows the dark matter distribution to be mapped out precisely by the inspiralling neutron star or small black hole.

In the earliest paper (Kavanagh, Nichols, Bertone and Gaggero), however, we noted that previous estimates of the change in the rate of inspiral assumed that the distribution of dark matter was static throughout the process. This assumption is not a good one for large changes in the inspiral rate, because the amount of energy input into the distribution of dark matter can be much larger than the total binding energy of the dark-matter spike. Thus, to make accurate predictions of the orbital dynamics, one must simultaneously evolve the distribution of dark matter with the binary’s orbit. The paper describes a method to do this for dark-matter distributions that remain spherically symmetric throughout the inspiral. We found that the rate of inspiral was much slower when the dynamics of the dark matter was taken into account. This mean that estimates of how well the dark matter could be measured through gravitational waves would need to be revised.

In the first follow-up paper (Coogan et al.), we addressed this question about the possibilities for detecting, discovering, and measuring the presence of dark matter in these IMRI systems. Gravitational waves from IMRIs with and without dark matter can be detected out to nearly identical distances by the planned space-based detector LISA. We then showed that searches for systems with dark matter with waveform templates that do not include dark-matter effects would lead to systems with dark matter being missed, because of reductions in the signal to noise. Finally, after developing a faster approximant to compute the waveforms, it was possible to compute the posteriors for the dark matter parameters using Bayesian inference. The density could be distinguished from zero even for systems near the threshold for detection. The Bayesian evidence ratio also favored the dark-matter hypothesis, when such waveforms were taken as the mock LISA data. If such IMRIs with dark matter form within the detection horizon for LISA, then they will be able to be distinguished from systems without dark matter.

In a subsequent work (Nichols, Wade and Grant), we investigated the effects of accretion of dark matter onto the secondary when the secondary was a black hole. We found that previous calculations of the amount of accretion onto the secondary were overestimates when the dark matter was assumed to be non-evolving as the secondary inspirals (specifically, because the amount of dark matter accreted would exceed the dark matter enclosed within the secondary’s orbit in certain scenarios). Adding in feedback from dynamical friction and evolving the dark-matter distribution decreased the amount of overestimate, but still did not account for the mass loss from the dark-matter density from accretion onto the secondary. We then derived and implemented a procedure to remove dark-matter particles from the dark-matter distribution so that mass was conserved. This led to smaller gravitational-wave effects from the accretion process, but there still were scenarios in which the effects of accretion were large enough that they would likely be measurable by the LISA detector, if such a system were observed.

In a fourth paper (Wilcox, Nichols and Yagi), we studied how well a commonly used framework to test general relativity against the predictions of modified theories of gravity (the parametrized post-Einsteinian framework) could be adapted to check for the presence of dark matter around IMRIs. If the distribution of dark matter were known to be spherically symmetric with a power-law falloff in radius, then the exponent in the framework could be fixed and unbiased parameter estimation could be performed. However, because it is unlikely that the dark-matter distribution would be known (and would follow a single power-law), then the exponent should not be fixed in the framework. When the exponent was not fixed, the recovery of the parameters had a large systematic error, which generally exceeded the statistical error. This work showed that dedicated gravitational waveforms from IMRIs with surrounding dynamical dark-matter distributions would likely be needed to analyze these systems without introducing significant systematic errors.

In the most recent paper (Wade and Nichols), we looked into the effect of different initial data on the dark matter effects on the binary’s orbit and the emitted gravitational waves. Previous studies had neglected the fact that dark-matter particles around the massive black hole would be rapidly captured onto the black hole, thereby decreasing the density of particles close to the massive black hole. This also has an affect on how the binary’s orbital dynamics influences the dark matter as it inspirals. We computed the difference between the earlier and our improved initial data for the dark matter, and we found that it has significant effects on the inspiral of the smaller black hole in the binary, especially when the more massive black hole is heavier. We also investigated when a binary evolves through the dark matter distribution following an earlier merger. This too could have a significant impact on the binary’s inspiral, which was larger when the first merger was for a lighter primary black hole.