Research Theme: Black-Hole Recoil Velocity and the Landau-Lifshitz Pseudotensor

This post is a summary of three papers I wrote towards the begining of my Ph.D. about gravitational recoils from merging binary black holes.

Papers Highlighted

-

G. Lovelace, Y. Chen, M. Cohen, J. D. Kaplan, D. Keppel, K. D. Matthews, D. A. Nichols, M. A. Scheel, and U. Sperhake. “Momentum flow in black-hole binaries: II. Numerical simulations of equal-mass, head-on mergers with antiparallel spins.” Phys. Rev. D 82, 064031 (2010), arXiv:0907.0869.

-

D. Keppel, D. A. Nichols, Y. Chen, and K. S. Thorne. “Momentum flow in black-hole binaries: I. Post-Newtonian analysis of the inspiral and spin-induced bobbing.” Phys. Rev. D 80, 124015 (2009), arXiv:0902.4077.

-

J. D. Kaplan, D. A. Nichols, and K. S. Thorne. “Post-Newtonian approximation in Maxwell-like Form.” Phys. Rev. D 80, 124014 (2009), arXiv:0808.2510.

Summary of the Papers

Two black holes in a circular orbit with their spin axes in the plane of orbit and pointed opposite each other (the superkick configuration) bob up and down together simultaneously once each orbit before they merge.

After colliding, the larger remaining black hole flies off perpendicularly to the orbital plane as a pulse of gravitational waves would head off in the opposite direction.

The speed of the remnant black hole depends sinusoidally upon the initial orientation of the holes’ momenta and spin axes; furthermore, it can be as large as a few percent of the speed of light.

Two black holes in a circular orbit with their spin axes in the plane of orbit and pointed opposite each other (the superkick configuration) bob up and down together simultaneously once each orbit before they merge.

After colliding, the larger remaining black hole flies off perpendicularly to the orbital plane as a pulse of gravitational waves would head off in the opposite direction.

The speed of the remnant black hole depends sinusoidally upon the initial orientation of the holes’ momenta and spin axes; furthermore, it can be as large as a few percent of the speed of light.

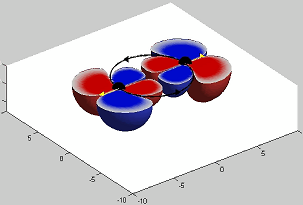

To understand how the bobbing motion before merger relates to the kick of the black hole after merger, we used the Landau-Lifshitz formulation of general relativity. In this formalism, the gravitational field is associated with a coordinate-dependent stress-energy tensor, the Landau-Lifshitz pseudotensor. The time-space components of the pseudotensor correspond to the momentum density of the gravitational field, which for weak gravitational fields, resemble those of the Poynting vector of electromagnetism. Here the gradient of the Newtonian potential plays the role of the electric field, and the gravitomagnetic field acts like the magnetic field. We defined a Landau-Lifshitz momentum of the black holes, and we found that the momentum of the black holes was exactly balanced by the field momentum near the black holes; moreover, the black holes’ momenta bob sinusoidally during each orbit.

We then investigated how the field momentum near the black holes relates to the asymmetric pulse of gravitational waves that gives the final black hole its recoil velocity. We studied a simplified model of the superkick configuration for this purpose: specifically, we simulated a head-on collision of two black holes with their spin axes anti-aligned and orthogonal to their separation. For black holes at large separations, weak-field calculations predict that the black holes will be pulled in the direction orthogonal to the plane of the black holes’ separation and spin axes (the numerical simulations confirm this). During merger, the momentum of the black holes smoothly reversed direction until the remnant black hole recoiled in the opposite direction of the transverse motion of the holes during their infall. We interpreted this process as a result of the black holes engulfing the momentum density as they merge.